The Two Heroines of Thalang (Salang)

The story of the Two Heroines of Thalang is deeply intertwined with the history of Phuket. In fact, Phuket’s identity as a tourist destination is partly built upon the legacy of these two sisters who successfully repelled a Burmese invasion in the 18th century. Their bronze statue, cast by Bangkok’s National Academy of Fine Arts and erected on the roundabout near Thalang in 1966, is perhaps the most photographed monument on the island.

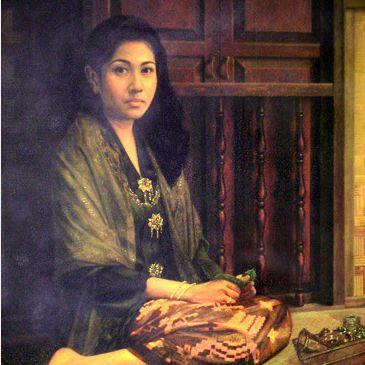

This account provides a brief overview of the events, based on information from the Thao Thepkrasattri-Thao Srisunthorn Foundation and other sources. The protagonists were sisters, Nang Jun and Nang Muk. Their father was the governor of Thalang, appointed by the Siamese capital of Ayutthaya, and their mother, Masia, was likely a princess or noblewoman from Kedah. Nang Jun was married to Phraya Salang, the district chief of Thalang.

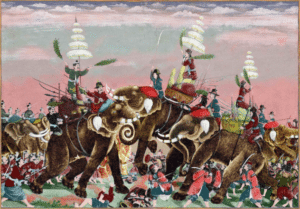

In 1785, Burmese forces invaded the west coast of Southern Thailand, including Phuket.

Following the death of her husband, Nang Jun, together with Nang Muk and a military officer named Nai Tongpoon, raised a defense army. To intimidate the invaders, Nang Jun devised a clever ruse. She assembled 500 women, dressed them as soldiers, and had them parade in various formations. This, along with the use of smoldering coconut husks that resembled muskets from a distance, successfully misled the Burmese regarding the strength of the defending forces. The women also actively harassed Burmese scouts and foraging parties. After a month-long siege, the Burmese army, demoralized and undersupplied, ultimately retreated, saving Phuket from occupation.

At the end of the war in 1786, King Rama I bestowed upon Nang Jun and Nang Muk the honorary titles of “Thao Thepkrasattri” and “Thao Srisunthorn” respectively. Nai Tongpoon was appointed the new “Phraya Thalang.” This historical episode, however, was only officially chronicled 35 years later during the reign of King Rama III (1824-1851).

Recent decades have witnessed a resurgence of national interest in the Two Heroines.

In 1985, Phuket governor Ouan Surakul visited the United Kingdom and brought back two letters written by Nang Jun to Francis Light, an agent of the British East India Company. These letters are now prominently displayed in the Thalang Museum’s Anglo-Thai section, highlighting this fascinating aspect of the legend. In 1992, the Thao Thepkrasattri and Thao Srisunthorn Foundation was established with funding from Princess Sirindhorn. The Foundation holds an annual commemorative ceremony for the two sisters on March 12th and lays a wreath at the foot of their monument on March 13th, designated as “Thalang Victory Day.”

Seated versions of the heroines’ statues can also be found at Wat Muang Komaraphat, a recently renovated temple near Bandon. It’s not uncommon to witness individuals whose wishes, believed to be granted by the heroines, have been fulfilled. These devotees often express their gratitude by sponsoring a “ronggeng” dance performance in front of the official monument. While Siamese Buddhists revere the heroines’ courage and leadership, Chinese Buddhists also pay their respects, often offering incense but refraining from pork offerings. This practice hints at a fascinating aspect of the heroines’ story.

While the sisters are venerated in a Buddhist temple that welcomes Chinese practices, the avoidance of pork offerings, traditionally considered unclean in Islam, suggests a different religious background. This discrepancy, however, is rarely acknowledged openly. Prasit Chinarkan, a respected Phuket historian, states, “We are not sure about their religion, they might have been Muslim, Buddhist or Christian.”

As with many historical narratives in Thailand, the possibility of the sisters’ Muslim identity remains shrouded in ambiguity, perhaps because it challenges the dominant narrative of Buddhist supremacy. However, members of Phuket’s Muslim minority, politically and economically disadvantaged, quietly maintain this belief. They argue that the sisters’ Muslim names, Fatimah and Halimah, have been deliberately obscured. Some even believe that the historical narrative was manipulated to portray the sisters as Buddhist.

Adding further intrigue to the story, members of the Phuket Islamic Council point to a humble graveyard nestled within a rambutan orchard, hidden from the main road. They believe this to be the site of an ancient “surau” (prayer house) where the sisters worshipped. A small incense burner sits between two prominent graves, said to belong to the heroines. Local lore claims that the elder sister, in her will (“wasiatkan”), requested to be buried facing the “surau.”

The Two Heroines of Thalang

Symbols in Contested Terrain

What do the Two Heroines represent in Phuket today? On the surface, they embody courage and ingenuity. Their story celebrates how the people of Thalang, despite limited resources, defended Phuket and, by extension, Siamese sovereignty against Burmese invaders, etching their place in Thai history.

Furthermore, the narrative reinforces the idea of local loyalty to the Siamese crown in a province already dominated by a Chinese majority in the 19th century. For the Chinese population, the Two Heroines serve as local deities, and visiting their shrine in Thalang is a way to express their own belonging within this multi-layered society.

However, for many Muslims who consider the heroines part of their own heritage, the popular narrative represents an appropriation of their history. The revelation of the sisters’ possible Muslim identities challenges the dominant narrative and highlights the complexities of identity politics in the region.

In his article “Ethnohistorical Perspectives on Buddhist-Muslim Relations and Coexistence in Southern Thailand: From Shared Cosmos to Emerging Hatred?” Alexander Horstmann notes the unique character of this region. Religions here have historically been accommodated and integrated into the social order and local cosmology. This was achieved through intermarriage, shared beliefs in common ancestors, syncretic healing practices, and a reciprocal respect for cultural niches. Even today, interfaith marriages, conversions between Buddhism and Islam, and the blending of rituals across religious lines continue to occur. This historical context sheds new light on the interfaith marriage of Nang Jun’s parents and challenges the simplistic categorization of the heroines’ religious identities.

While older generations of Thai Buddhists and Muslims might not have viewed the heroines through an exclusive religious lens, contemporary interpretations tend to be more partisan. This struggle for ownership of cultural icons reflects deeper anxieties around identity and belonging.

A commonly heard phrase in the region, “Surau kap wat, non gnat kanai (surau or wat, where should I go?)”, aptly captures this sense of ambivalent identity, as shared by local historian Pranee Sakulpipatana. The choice between the “wat” (Buddhist temple) and the “surau” (Muslim prayer house) represents a symbolic alignment with either a Siamese Buddhist or a Malay Muslim identity.

Dr. Bradley, who visited Phuket in 1870, recorded a population comprising 200 Malays, 300 Siamese, and 200 “Siamese-Malays,” alongside a Chinese majority. The term “Siamese-Malay” perhaps provides a key to understanding the complexities of Thai Muslim identity in this region. [Gerini, 1986 (1905)]

Local histories in places like Phuket and Southern Thailand often reveal the ambiguities of identity construction. Just as the religious background of the Two Heroines is contested, so too are the origins of place names. A Muslim resident of Phuket recounts his maternal grandmother’s words: “The old people always called the ports Bunga, Bukit and Terang. Now they call them Phang Nga, Phuket and Trang.”

The name “Phuket,” like the old name “Junk Ceylon,” has at least two possible etymologies. The common explanation links it to “bukit,” the Malay word for “hill.” The name was indeed spelled “Bhuket” until officially changed in 1967. However, an old Siamese document transcribes the name as “phukej,” meaning “gem,” an interpretation favored by some to assert a Siamese origin for “Phuket.”

With Siamese names historically recorded in Thai script and Malay names written in Jawi or Arabic, definitively proving the antecedence of one over the other is near impossible. While the Thai perspective often denies a Malay origin for “Phuket,” many educated Muslims perceive these naming practices as a form of cultural erasure, part of a larger pattern of appropriating Malay place names, history, and language that has occurred within living memory.