This post is also available in:

![]() Français

Français ![]() Русский

Русский

Phuket's Thai Muslims

A Community In Between

Phuket has a long history of trade with Malay merchants, particularly from Kedah. Captain Thomas Forrest, writing in the late 18th century, observed that Phuket’s inhabitants generally spoke Malay due to “their commerce with that people.” Coastal Muslim communities in Krabi and Trang maintain family ties with relatives in Kedah, Langkawi, and Penang in Malaysia. While previous generations were predominantly Malay-speaking, today, the situation is more complex.

Almost all Muslims in Phuket over the age of 50 or 60 speak Thai as their first language, a stark contrast to the “deep south” provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat, where the dominant language is a Malay dialect called “Jawi” (similar to Kelantanese).

So who are Phuket’s Thai Muslims today? Their identity cards classify them as “Thai nationality, Islam religion,” like other Thai Muslims in the south. Buddhist Thais often refer to them as “Is-salam,” while within Thailand, all Muslims are categorized as “Thai Muslim,” regardless of their ethnic background. Like their Muslim names, they carry Sanskrit-based Thai names used for public life. While fluency in Malay might have once been a strong ethnic marker, this is no longer the case, and most do not identify as Malay.

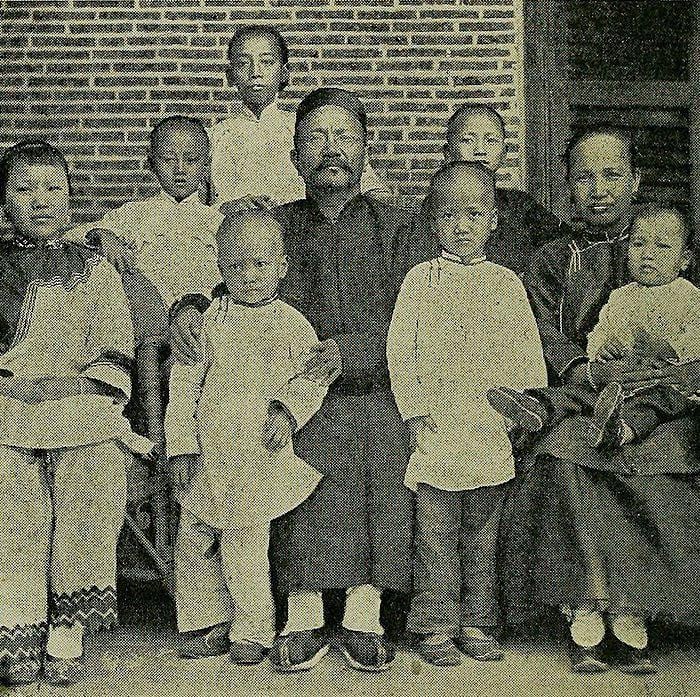

The Muslim community in Phuket Town is diverse, encompassing Thai Muslim merchants alongside those of Arab, Afghan, Pakistani, Indian, and Chinese descent, as well as Malay traders from other southern provinces. Coastal communities, particularly those with roots in Langkawi, likely arrived in Phuket as impoverished seafaring migrants. Census data from the 19th century suggests that most Thai Muslims settled in Phuket during that period, although many originated from nearby coastal areas.

In her work, “The Politics of Forgetting: Migration, Kinship and Memory on the Northern Malay periphery,” Janet Carsten describes the inhabitants of a Langkawi fishing village as engaging in “a collective denial of shared identity formation.” It’s plausible that a similar dynamic exists among coastal Thai Muslims in Phuket.

In today’s globalized world, Thai Muslims are experiencing an Islamic revival. Phuket boasts 50 mosques, with the largest Islamic school, Muslim Wittaya School on Thepkasattri Road, catering to 1,300 students from kindergarten to high school. Many students further their Islamic education in Pattani, Yala, or Narathiwat.

The situation of Phuket’s Thai Muslims reveals a community navigating the complexities of identity. Caught between their Malay heritage, their Thai citizenship, and their Islamic faith, they represent a microcosm of the cultural and religious tapestry of southern Thailand.

Muslim Coastal Villages Turn to Tourism

Although Thai Muslims are scattered throughout Phuket, they constitute the majority only in Bang Tao and Kamala, situated on Phuket’s west coast north of the bustling tourist hub of Patong.

Thai Muslims rarely feature prominently in the vast literature on Phuket tourism, often relegated to images of fishermen in their longtail boats. They have traditionally engaged in occupations like orchard farming and rubber tapping.

During the tourism boom of the 1980s, many Phuket Muslims, like their Malay counterparts in Langkawi a decade later, sold their land to property developers. It’s hard to imagine now, but they once owned up to 60% of the land in Bang Tao, Kamala, and Patong, all now prime tourist beaches.

Today, Kamala, with a population of 6,000, is officially classified as a Thai Muslim sub-district. It is estimated that 80% of residents are Muslim, with the remaining 20% being Buddhist. A significant 75% of the population is employed in the tourism industry.

Kamala’s full-fledged immersion into tourism began with the opening of “FantaSea” in 1998, a lavish 3.3 billion baht entertainment complex. A subsidiary of Bangkok’s Safari World, FantaSea was realized through a joint venture with a local landowner who mortgaged his 350 rai (56 hectares) property to secure funding. Employing over 1,000 people, including many Kamala residents, it attracts thousands of visitors nightly.

The presence of FantaSea cemented Kamala’s trajectory towards mass tourism. The Kathu District administration has already designated an entertainment zone in Kamala, encouraging the proliferation of businesses like bars, discos, and karaoke lounges. (Phuket Gazette, June 5, 2001)

Said Wissanu Doomlak, a Thai Muslim politician from Kathu: “Many people are selling their land to foreigners. In 10 years, Kamala beach will look like Patong. The locals will be driven away to live in the hills, and only the Muslim cemetery by the beach will remain as a reminder of their presence here.”

Tragically, during the 2004 tsunami, Kamala and Patong beaches suffered the highest number of casualties along Phuket’s coast, accounting for 279 out of the total deaths.

While foreign-owned establishments in Patong have been quick to recapitalize, the small-scale guesthouse owners in Kamala lack the resources to rebuild.

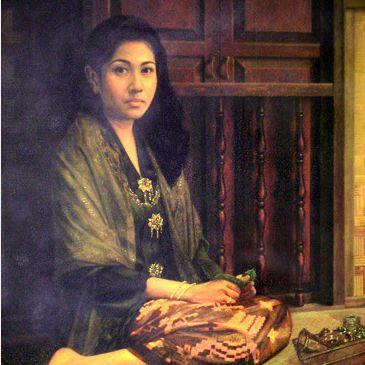

In July 2005, in an effort to attract tourists back to Kamala, a Muslim food festival was held, highlighting the legend of Mahsuri as a cultural attraction. This legend gained local prominence some years earlier when a local family was identified as descendants of the mythical Malay heroine.

The story of Kamala exemplifies the complex relationship between tourism development and the lives of local communities. The influx of tourism brought economic opportunities but also triggered significant social and cultural changes, leading to anxieties about land ownership, cultural preservation, and the very identity of Kamala itself.