This post is also available in:

![]() Français

Français ![]() Русский

Русский

MAHSURI of LANGKAWI

This second historical narrative regarding Mahsuri takes us to Langkawi, an archipelago belonging to Kedah, Malaysia. Known to Phuket locals as “Koh Kawee,” Langkawi, with its dramatic limestone cliffs, is steeped in pre-Islamic myths. The most famous among these is the legend of Mahsuri.

Though involving historical figures, the legend of Mahsuri also delves into the realm of the mystical. Passed down orally for generations, it was only transcribed in recent times. In 1988, the Kedah Historical Society documented over 30 versions of the legend (Hari Sastera Kedah, 1989).

The story tells of Mahsuri, a beautiful maiden who married a nobleman named Wan Darus. When her husband was called away by the Sultan of Kedah, Mahsuri was falsely accused of adultery in his absence. Wrongfully convicted by the local chieftain, she endured multiple failed execution attempts before finally succumbing to a stab wound. Witnesses claimed that white blood flowed from her body.

This “white blood” became a symbol of her innocence. With her dying breath, she cursed Langkawi for seven generations. Ironically, the island now capitalizes on this curse, turning Mahsuri’s alleged tomb into the central attraction of a sprawling tourist complex – the “Mahsuri Complex.” Replete with signs and information boards in Malay, the complex primarily caters to busloads of conservative Malaysian tourists.

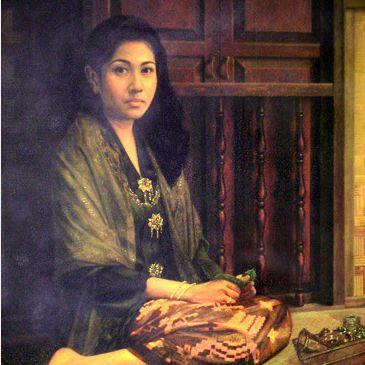

Built around the frequently reconstructed tomb of Mahsuri, the complex houses a museum, performance hall, a traditional village setting, souvenir shops, and restaurants. Images of Mahsuri, rendered according to Malay beauty standards, adorn the site.

Interestingly, this glorification of Mahsuri’s tomb seems to have escaped the ire of Islamic modernists, who typically oppose such veneration practices, deeming them “grave worshipping.” This folk tradition, often linked to Sufism, is generally frowned upon by orthodox Muslims.

Perhaps Malaysian tourists visiting the complex view the legend through the lens of a classic Malay romantic tragedy. However, many elements of the story – the mystical “white blood,” the heroine’s near-invincibility, the curse doubling as a reversed prophecy, the symbolism of the number seven, the charismatic tomb, the idealized female iconography, and, as we’ll explore later, the underlying concept of reincarnation – fall outside the realm of orthodox Islamic discourse. Such beliefs, however, resonate deeply in southern Thailand, where Mahsuri’s legacy finds fertile ground.

Central to understanding the legend is the magical significance of “white blood,” a motif echoed in other regional tales like the “Legend of the White Semang” (Winstedt and Wilkinson: 1974, 196-202), the legend of Putri Sa’dong in Kelantan, and the legend of Putri Lindungan Bulan in Kedah.

In her essay, “In the Realm of the White Blood Lady: Southern Thailand and the Meaning of History,” Lorraine M. Gessick examines the “Nang Lued Khao” manuscript, which recounts the origin story of Phatthalung. Both Perak and Kedah, only brought under British rule in 1875 and 1909 respectively, seem to exist within this shared mystical landscape.

While “white blood” symbolizes nobility in Phatthalung and Perak, in the cases of Putri Sa’dong, Putri Lindungan Bulan, and Mahsuri, it represents innocence and moral superiority over their accusers.

With this connection to southern Thailand established, we can reexamine the legend of Mahsuri. Her tragedy might stem from a cultural clash between two distinct Muslim societies. Seven generations ago, Islam was not widespread in Phuket, whereas Arab Hadhrami traders had already established a presence in Langkawi and Kedah. It is conceivable that Mahsuri’s social conduct, deemed acceptable in her own community, was perceived as transgressive by the more orthodox families of Langkawi.

Siamese Muslims, now Thai-speaking, remain on the periphery of the larger Malay-speaking Muslim world. Differing cultural norms can lead to misunderstandings, and in Mahsuri’s case, the price of such a misunderstanding was death. Her people returned to southern Thailand, a region with its own unique origin myths and cultural ethos. There, they continue to exist at the edges of the “Malay World.”

The Yayee Family of Kamala

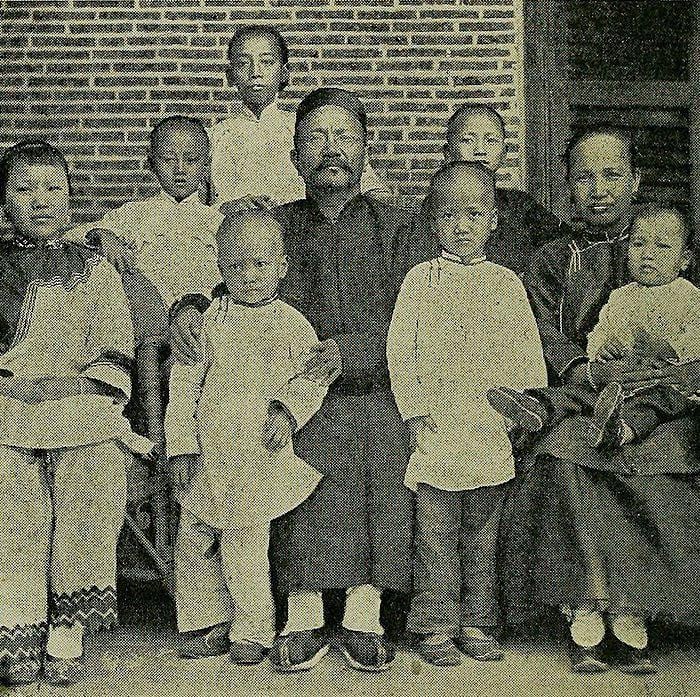

In Kamala, a prominent clan claims direct descent from Mahsuri and Wan Darus. They believe that Mahsuri’s son, Wan Arkem (or Achem), was brought to Kamala, where he married and had six children – two sons and four daughters. Their Thai-speaking descendants, comprising six sub-clans in Kamala, carry four distinct surnames: Yayee, Doomlak, Samerpurn, and Sangwan.

Among them is Sirintra Yayee, believed to be the seventh-generation descendant of Mahsuri, according to the findings of the Kedah Historical Society in 1988 (Hari Sastera Kedah, 1989). In 2000, at the age of 14, Sirintra, accompanied by her 62-year-old grandfather Chern Yayee, was whisked away to Malaysia to meet then Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir Mohamad. The meeting generated headlines in both Thai and Malaysian newspapers, with some articles commenting on Sirintra’s striking resemblance to portraits of Mahsuri (Phuket Gazette, May 19, 2000).

More recently, Sirintra received a scholarship from Utusan Malaysia to study communications at the International Islamic University in Kuala Lumpur. Now 19, she reflects on her unique position with a mix of wonder and sadness: “It’s great that they (Malaysians) acknowledge and accept me, but sometimes I don’t understand why they didn’t accept her (Mahsuri).”

Sirintra was the star attraction at Kamala’s Halal Festival, featuring in a light and sound presentation titled “The Story of the Legendary Muslim Princess Mahsuri.” The bilingual program described the performance as: “A 200-year-old tragic legend full of love, sacrifice, hope, and curses of Princess Mahsuri who lived in Kemala village and married the Prince of Langkawi, Malaysia. The legend has recently resurfaced at Kamala, where her 7th generation descendant, Miss Sirintra Yayee, was born to break the curse. This phenomenon creates strong cultural links between the two areas, Langkawi in Malaysia and Phuket in Thailand.”

While Mahsuri is primarily associated with Langkawi, her legend holds a different significance in Phuket. It possesses the potential to become a unifying narrative for the entire Thai Muslim community in Phuket, at least within the realm of tourism promotion.

Given the lack of a dedicated monument to Thai Muslim heritage in Phuket, the proposed Mahsuri Museum, likely to be located within the FantaSea complex, could become the island’s premier Thai Muslim cultural attraction.

The legend holds significant appeal for both the community and Phuket’s tourism industry. The romantic tale of a beautiful woman falsely accused and unjustly treated resonates with audiences across religious and cultural backgrounds. It offers a counter-narrative to the often-stereotypical portrayal of Thai Muslims in the media, particularly in the aftermath of 9/11 and the ongoing conflict in southern Thailand, challenging the image of the “Muslim militant.”

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge the potential pitfalls of commodifying such a culturally and religiously significant narrative for tourism purposes. The challenge lies in striking a balance between promoting understanding and respect for Thai Muslim heritage while avoiding the exploitation and trivialization of a deeply cherished legend.

Halal Food, Hilal Town

The “Halal Food, Hilal Town” Festival, mentioned earlier, was promoted by the Tourism Authority of Thailand as a celebration of diversity. Their official statement read: “In order to create a better understanding of the island’s cultural diversity and rich heritage, the Phuket Provincial Administrative Organisation is holding Halal Food, Hilal Town, a cultural showcase of Thai Muslim art and culture, traditions, folklore, and way of life.”

The “Halal Food, Hilal Town” Festival, mentioned earlier, was promoted by the Tourism Authority of Thailand as a celebration of diversity. Their official statement read: “In order to create a better understanding of the island’s cultural diversity and rich heritage, the Phuket Provincial Administrative Organisation is holding Halal Food, Hilal Town, a cultural showcase of Thai Muslim art and culture, traditions, folklore, and way of life.”

Held in Kamala from July 28th to August 1st, 2005, the festival opened with the symbolic release of 39 doves representing a call for peace in southern Thailand. The main attraction was a food fair offering “a delicious array of Halal food prepared according to Muslim rites.” The festival also provided a rare opportunity to witness a diverse range of Muslim and Malay cultural performances.

These included:

Likay Ulu, a Thai version of Dhikir Barat, presented by the Kempulan Bungayaran group from Pattani.

Silat Gayong, a martial art demonstration from Krabi

Wayang Kulit, shadow puppetry from Nakhon Sithammarat

Ronggeng, a traditional dance performed by a group of elderly Orang Laut women from Koh Sirey

Lekia (Malay) or Khun Ple (Thai), a percussion-based ritual for newborns, performed by the last remaining Lekia group in Phuket, a group of elderly men from Bang Tao.

Khun Charoen Thinkohkeow, a Muslim advisor to the provincial government, played a key role in selecting the performing groups. He emphasized the distinct cultural identity of Thai Muslims: “Islamic culture is not just Arabic; we have our own traditional Thai Muslim culture.” Khun Charoen is also the manager of “FM 94” radio station and an advisor to Phuket’s Muslim Wittaya School.

Interestingly, several Islamic groups participating in the festival had stronger ties with Malaysia than with southern Thailand. For example, the “Nasyid” (Islamic devotional songs) girls and “Kompang” (hand drum) boys from the Islam Pattanah group originated from the Thai branch of the Malaysian Mawaddah organization. This organization traces its roots to Rufaqa, a reformed and reconstituted offshoot of the Al-Arqam group, previously banned by the Malaysian government.

The festival received substantial financial support, estimated between five and six million baht, from the Democrat-led Phuket Provincial Government. Khun Anchalee, the Chief Executive, outlined the event’s threefold objective: to help Kamala rebuild after the tsunami, to attract Middle Eastern tourists, and to demonstrate to the world that Thai Muslims and Buddhists can coexist peacefully.

Addressing concerns about Halal food standards, Khun Charoen explained, “Tourists from the Middle East have doubts about the Halal status of food in Phuket, questioning whether it’s truly Halal or ‘mashbooh’ (doubtful).” Chulalongkorn University’s Halal Science Center was invited to train vendors, ensuring that food served met the expectations not only of Arab tourists but also other Muslim visitors, particularly Malaysians and Indonesians.

However, the festival carried implications beyond its stated objectives. Inaugurated by Privy Councillor General Surayud Chulanont, it served as a platform for prominent Democrat party figures, including former Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai and Khun Suthep Tuaksubhand, Secretary-General of the Democrat Party and MP for Suratthani, to connect with the predominantly Muslim audience from southern Thailand.

Chuan Leekpai, a veteran Democrat leader from Trang, is widely regarded as a political icon in the south. Speaking at the festival, he criticized Thaksin Shinawatra’s policies, which he claimed had exacerbated tensions between Muslims and Buddhists in the south. He contrasted this with his own experience visiting a Buddhist temple in Kelantan, where Thai Buddhists expressed no issues coexisting with Malay Muslims in Malaysia. His message resonated strongly with the local Muslim population.

Phuket’s Thai Muslims are grappling with complex questions of identity – as a minority within a predominantly Buddhist nation, as Thai speakers in a region where Indonesian or Malay dominates, and as Muslims increasingly integrated into the world of beach tourism.

Those living in Kamala and those catering to beachgoers face a constant negotiation between the forces of Arabization and conservative Islamic revivalism sweeping the Muslim world and the liberal, modern influences of the “decadent” tourism industry.

The “Halal Food, Hilal Town” Festival (in Arabic, “Makolat Al-Halal, Madinah Al-Hilal,” with the latter translating to “Crescent City”), offered both the Muslims of Kamala and the provincial government an opportunity to reimagine Kamala as a haven for Halal cuisine and Muslim tourists.

While it is challenging to envision an alternative to an economy heavily reliant on tourism, there might be opportunities to attract a different kind of hedonistic traveler, one ## Halal Food, Hilal Town: More Than Just a Festival?

The “Halal Food, Hilal Town” Festival, promoted by the Tourism Authority of Thailand as a celebration of Phuket’s diverse heritage, was more than just a cultural showcase. Held in Kamala from July 28th to August 1st, 2005, it represented a complex interplay of cultural preservation, political maneuvering, and economic aspirations in a community grappling with its identity.

The festival, with its symbolic release of doves, vibrant performances showcasing Thai Muslim art forms, and a delectable array of Halal cuisine, aimed to offer a counter-narrative to the often-negative portrayals of Thai Muslims in the wake of 9/11 and the escalating violence in southern Thailand.

However, the event also served as a strategic platform for the ruling Democrat party to connect with the predominantly Muslim audience of southern Thailand. The presence of high-profile Democrat figures, including former Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai, highlighted the party’s commitment to inclusivity and peaceful coexistence, subtly contrasting it with the policies of then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, which were perceived by many as exacerbating religious tensions.

The festival’s focus on “Halal Food” and the use of “Hilal Town” (Crescent City) in its title, hinted at a more significant aspiration – to position Kamala as a prime destination for Muslim tourists. This ambition reflects the community’s search for economic opportunities beyond the mainstream, often exploitative, tourism industry.

Several layers of complexity underpin this aspiration. Firstly, it highlights the tension between catering to a globalized, predominantly Western tourist market and preserving the cultural and religious identity of a community caught in between. The presence of Islamic performance groups with stronger ties to Malaysia than to southern Thailand further underscores this intricate web of influences.

Secondly, it reveals the ongoing struggle of Thai Muslims to define their place within a predominantly Buddhist nation. By embracing their unique cultural heritage and promoting Halal tourism, they are not only seeking economic empowerment but also asserting their right to exist and thrive within the multicultural fabric of Thai society.

The “Halal Food, Hilal Town” Festival, therefore, transcended its immediate objective of promoting cultural understanding. It offered a glimpse into the complex realities of a community negotiating its identity, its aspirations, and its place in a rapidly changing world, all while navigating the turbulent waters of Thai politics and the ever-evolving landscape of global tourism.