This post is also available in:

![]() Français

Français ![]() Русский

Русский

Once Upon a Time in Phuket

Shifting Identities of Chinese Peranakan and Thai Muslims in the Tourist Haven of Phuket

Khoo Su Nin (Salma) Nasution

Problem

The way a nation-state defines its population is largely top-down, leaving little room for communities, especially minorities and those in the provinces, to assert their own identities. However, many governments take tourism seriously, allocating significant resources to tourism development. Participation in cultural tourism then becomes an avenue for these communities to project their identities in a politically unthreatening way, thereby gaining recognition from the state.

While the Thai nation-state exerts a strong cultural hegemony, it leaves little space for local cultural nuances in Phuket to develop a historical narrative in sync with its own social memory. Yet, this local history is often used to reaffirm, enrich, and elevate identity in a sociocultural context. This paper will examine three particular historical narratives associated with Phuket and try to understand what they represent. It will also look at two contemporary phenomena where communities have mobilized ways to project their history, traditions, and identity to a tourist audience.

Background

Phuket is a province in Southern Thailand where a Southern dialect is spoken, marking a proud distinction from the north. One of the 14 Southern provinces of Thailand, Phuket encompasses 39 islands situated in the Andaman Sea. The largest island in Thailand, Phuket covers an area of 570 square kilometers, roughly the size of Singapore.

The 2000 census recorded a population of 249,000, but the actual figure is believed to be closer to half a million at the end of 2004, the discrepancy due to the omission of a significant urban-based Thai expatriate population and the Burmese workforce community. Thais comprise 98.5% of the population, of which 81.6% are Buddhist and 17.1% Muslim.

Christians and sea gypsies (including the “Orang Laut”) constitute only 1% each. No distinction is made between Thais and Sino-Thais as they all hold Thai citizenship and practice Buddhism as their religion. The percentage of Muslims is down sharply from the 35% noted in a 1980 report which also recorded 29 mosques, 28 Thai temples, a dozen Chinese temples, four Christian churches, and one Sikh temple.

Three Historical Narratives

Phuket’s establishment as a resort island can be traced back to the 1970s. Before that period, Phuket was simply a trading port. Since the sixteenth century, western cartographic sources have indicated the island as “Jungceylon” (with various spellings), undoubtedly derived from the Malay name “Ujong Salang” or “Tanjong Salang,” literally meaning the tip or cape of Salang. Of the many historical facts about Phuket that one can narrate and which are promoted by the authorities, three stand out.

The first narrative relates to the two national heroines of Salang who led the resistance against Burmese invasion.

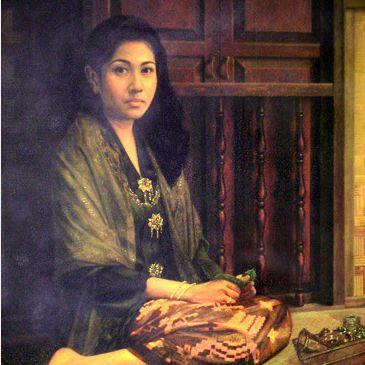

The second narrative refers to the legend of Mahsuri, celebrated in Langkawi and whose origins are believed to be traceable to the Thai Muslims of Kamala.

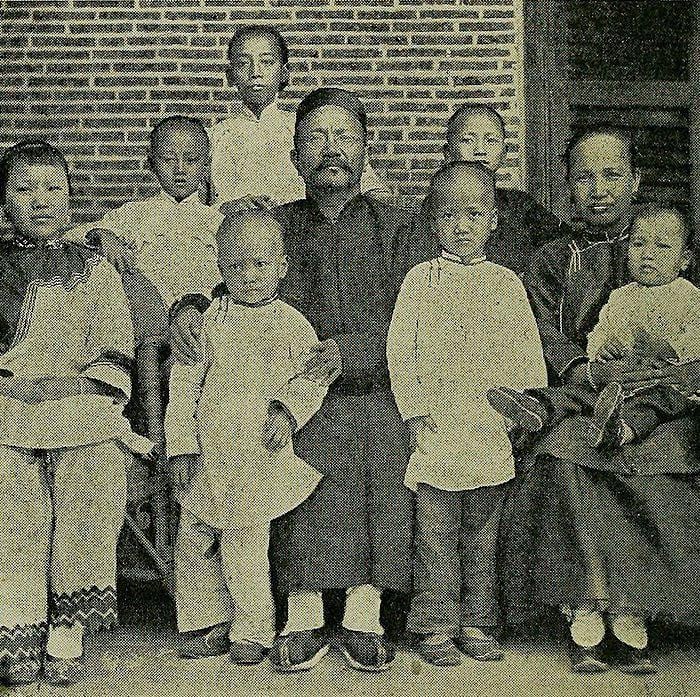

The third recounts the more complex story of the building of Phuket Town by Hokkien (“Fujian”) emigrants and how it was wisely governed by a Chinese headman loyal to the king.

The government’s support in promoting these three historical narratives clearly reflects its recognition of the three communities established in Phuket. In practical terms, this translates into development funds being channeled to the three local administrations situated in different parts of the island.